Starting with an Intuitive Problem

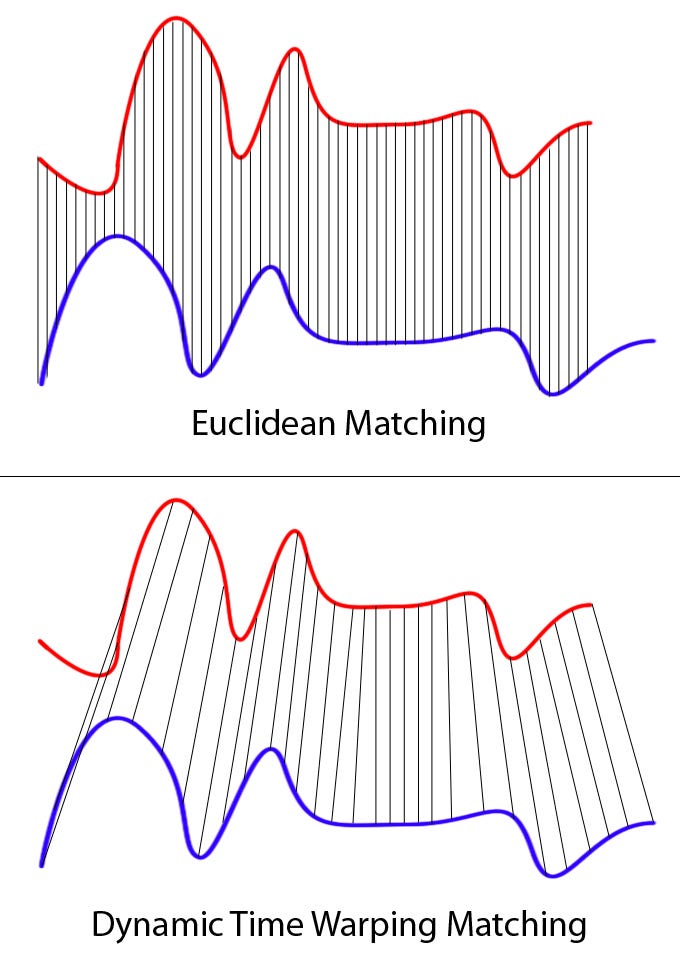

When processing audio, speech, or other time series data, we will almost certainly encounter this problem: if two signal segments are similar in “content,” but not consistent in the speed of time progression, can we still judge that they are similar?

This problem is very common in real scenarios. For example, two people sing the same melody, but one sings faster and the other slower; students may slow down due to hesitation during sight-singing, retreat and re-sing after making mistakes, or suddenly accelerate at certain positions; the same sentence is spoken by different people with different speaking speeds and different pause patterns. In these cases, if we rigidly require “frame 1 matches frame 1, frame 2 matches frame 2,” then almost all real samples will be simply and crudely judged as “not similar.”

DTW (Dynamic Time Warping) was proposed precisely to solve this type of problem where “time axes don’t match, but content is essentially similar.” It focuses not on whether time points are strictly consistent, but on: whether two sequences can be reasonably corresponded under the premise of allowing time to stretch and compress.

Core Idea of DTW: Allowing Time to Be Stretched

From an intuitive perspective, the idea of DTW is not complicated. It does not require two sequences to advance synchronously in time, but allows one sequence to “go faster” in some places and “go slower” in others, as long as the overall trend and shape are as consistent as possible. In other words, DTW focuses on “whether the shape is similar,” not “whether the time is aligned.”

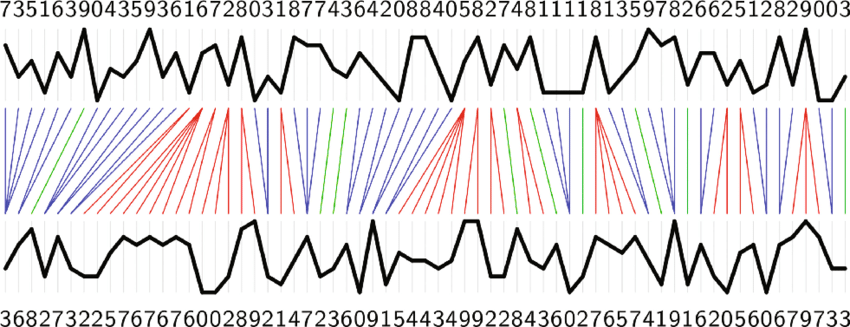

Mathematically, we usually represent two time series as:

\[ X = (x_1, x_2, \dots, x_N), \quad Y = (y_1, y_2, \dots, y_M) \]Here, \(x_i\) and \(y_j\) are not raw audio sampling points, but feature frames extracted at the \(i\)th and \(j\)th time positions. It should be noted that the sequence lengths \(N\) and \(M\) are not required to be equal, which itself already reflects the idea of “time does not need to be synchronized.”

Next, DTW constructs a distance matrix of size \(N \times M\):

\[ D(i, j) = \lVert x_i - y_j \rVert \]You can think of this matrix as a comprehensive reference table: it answers the question, “How different is the state of sequence X at the \(i\)th moment from the state of sequence Y at the \(j\)th moment?” Each cell in the matrix is a potential “alignment choice.”

“Walking a Path” in the Distance Matrix

DTW is not simply finding a minimum value in the distance matrix, but searching for a path from the upper-left corner to the lower-right corner in the entire matrix. The upper-left corner \((1,1)\) represents the starting point of the two sequences, the lower-right corner \((N,M)\) represents the endpoint of the two sequences, and each cell passed through on the path represents a decision of “aligning the \(i\)th frame to the \(j\)th frame.”

This path is not arbitrary; it must satisfy three very intuitive constraints. First is monotonicity: time can only advance forward, not return to the past; second is continuity: each step of the path can only move to adjacent positions, not jump; finally is boundary conditions: the path must completely cover both sequences, not only align part of them.

Under these constraints, DTW seeks a path with minimum cumulative distance:

\[ \mathrm{DTW}(X, Y) = \min_{W} \sum_{(i,j)\in W} D(i,j) \]Where \(W\) represents a legal alignment path. Intuitively, this path describes “which alignment method can make the two sequences most similar overall if time is allowed to be stretched or compressed.”

A More Intuitive Analogy

You can imagine DTW as this process: two people respectively walked out a string of footprints on the ground, one walked fast with larger spacing between footprints; the other walked slowly with dense footprints. If you require “the 5th footprint of the first person must correspond to the 5th footprint of the second person,” then it is almost impossible to align. But if certain footprints are allowed to be “stretched” or “compressed,” as long as the overall walking direction is consistent, then a reasonable correspondence can be found. DTW is doing exactly this, except that footprints become feature frames, and the alignment process is formalized as a path search problem.

Is DTW Applicable to Sight-Singing Tasks?

In sight-singing tasks, a frequently raised doubt is: “Isn’t DTW algorithm too old?” But in fact, this is not the key to the problem. The core assumption of DTW is very simple: two sequences are essentially similar, only the way time progresses is different. It does not care whether pitch falls on standard pitch levels, nor does it require rhythm to be absolutely stable, and it will not actively exclude glissando, vibrato, or unstable attack processes.

Therefore, in sight-singing tasks, what really determines whether DTW is “useful” is not the algorithm itself, but: in what way do we describe students’ singing behavior.

A Common Reason for Failure

Many conclusions that “DTW is not applicable to sight-singing tasks” often stem from a hidden but fatal logical chain: students’ singing behavior itself is continuous, fluctuating, and full of unstable details, but the features we choose assume that pitch is discrete, regular, and stable. The result is that DTW is forced to do alignment in an already distorted representation space, and naturally arrives at the conclusion that “the effect is not good.”

This is not a problem with DTW, but using an inappropriate ruler to measure an object that is itself irregular.

What are Feature Frames?

In DTW, “feature frames” are not an optional implementation detail, but the prerequisite of the entire alignment process. DTW itself does not understand “sound,” “melody,” or “pitch”; what it can handle is always just a vector sequence. In other words, DTW aligns not audio, but some description you make of the audio.

In form, we usually assume: every \(\Delta t\) seconds, features are extracted from the audio once, using a \(d\)-dimensional vector to represent the sound state during this short period:

\[ x_i \in \mathbb{R}^d \]Where \(i\) is the time index and \(d\) is the feature dimension. An entire audio segment will ultimately be represented as a vector sequence that changes over time:

\[ X = (x_1, x_2, \dots, x_N) \]All calculations done by DTW occur entirely in this sequence space. It neither knows that these vectors come from human voice, nor knows which note they correspond to; the only thing it can do is judge “whether the \(i\)th frame and the \(j\)th frame are similar” based on the distance metric you define.

Therefore, a very critical but often overlooked fact is:

The upper limit of DTW’s capability is completely determined by the expressive power of feature frames.

From “Continuous Sound” to “Discrete Frames”

Real sound changes continuously in time, while feature frames are discrete sampling of this continuous process. This process itself implies a “modeling assumption”: we default that within such a short time \(\Delta t\), the state of sound is relatively stable and can be approximately represented by a vector.

You can compare this process to animation production: the naked eye sees continuous movement, but animation is actually composed of frame-by-frame static pictures. What information each frame retains directly determines whether you can restore the original action. The same is true in audio analysis: feature frames determine which aspects of sound you actually “see” and which aspects you ignore.

Feature Frames Are Not Just “Features,” But a Hypothesis

In many introductory materials, feature frames are often introduced as “compressed representation of audio,” but in the context of DTW, a more accurate statement is: every type of feature frame implies a set of assumptions about sound behavior.

These assumptions include but are not limited to:

- Which attributes of sound are important;

- Which changes can be ignored;

- Which changes should be viewed as “errors”;

- Between different time points, what kind of difference is “similar.”

Once these assumptions do not match the actual singing behavior, then even if the DTW algorithm itself is completely correct, the final alignment result will inevitably fail.

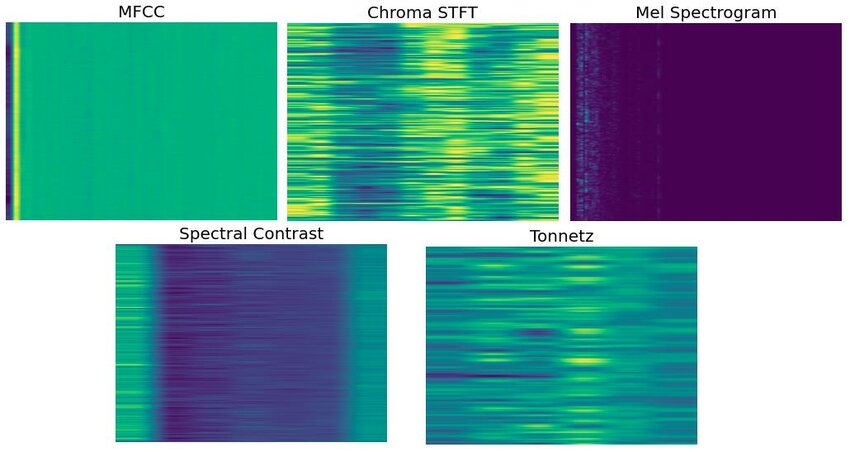

Common Feature Frames and Their Implicit Assumptions

Below we look at several feature frames commonly used in time series alignment tasks, and focus on analyzing what kind of sound worldview each defaults to.

MFCC: Assuming “Timbre More Important Than Pitch”

The core goal of MFCC (Mel-Frequency Cepstral Coefficients) is to characterize the overall spectral shape of sound. Its classic calculation process can be written as:

\[ \text{MFCC} = \text{DCT}(\log(\text{MelSpectrum})) \]From the design intent, MFCC is more concerned with “what this sound sounds like” rather than “what pitch this sound is.” It performs excellently in speech recognition precisely because when different people say the same word, pitch may vary greatly, but timbre and resonance structure often have consistency.

But in sight-singing tasks, this advantage actually becomes a problem. Whether students sing accurately and whether interval relationships are correct is precisely the information we care about most, and MFCC actively weakens details related to absolute pitch in the calculation process. The result is: even if students’ overall pitch shift is obvious, the distance between MFCC sequences may still be small, thus misleading DTW into thinking that the two performances are “similar.”

Chroma: Assuming Pitch Is Discrete and Stable

Chroma features compress the frequency axis to 12 pitch classes. Its basic form can be written as:

\[ \text{Chroma}(k) = \sum_{f \in \text{pitch class } k} |X(f)| \]This representation implies a very strong premise: at any moment, sound can be clearly classified into a certain pitch class. In tasks such as instrument performance and harmonic analysis, this assumption often holds, so Chroma performs well in these fields.

But in student sight-singing, the reality is often exactly the opposite. Pitch may continuously wander between pitch classes, the attack phase is unstable, and glissando and vibrato appear frequently. In this case, Chroma features will jump back and forth between adjacent pitch classes, making the time series itself present a highly irregular form. DTW does not know this is “natural fluctuation of human singing”; it can only see a constantly shaking discrete symbol sequence.

Continuous Fundamental Frequency (F0): Representation Closest to Real Singing Behavior

If the fundamental frequency trajectory is directly used as a feature frame, then each frame can simply be represented as:

\[ x_i = f_0(t_i) \]Or further convert to cent scale:

\[ x_i = 1200 \cdot \log_2\left(\frac{f_0(t_i)}{f_{\text{ref}}}\right) \]This representation method makes almost no prior constraints on pitch. It allows pitch to change continuously and also allows deviation near the target note, so it can naturally express glissando, vibrato, off-pitch, and unstable attack processes. From a modeling perspective, its distance from real singing behavior is the closest.

It should be noted that the problem with F0 representation is mainly not whether “the assumption is reasonable,” but at the engineering level: noise interference, fundamental frequency estimation errors, vocal register switching, and handling of unvoiced segments will all affect the stability of feature sequences. But these problems belong to the category of signal processing and system design, not structural defects of DTW itself.

The Real Relationship Between Feature Frames and DTW

After understanding the assumptions of different feature frames, we can return to a very important but often overlooked conclusion:

DTW will not correct wrong representations; it will only faithfully align what you give it.

If the feature frame itself cannot express students’ real singing behavior, then DTW is only seeking “optimal but still wrong” paths in a distorted space. Conversely, as long as features allow continuous changes and unstable processes, DTW actually becomes an extremely natural, almost intuitive time alignment tool.

Summary: The Real Question to Ask

In sight-singing tasks, what is really worth thinking about repeatedly is not “whether to use DTW,” but: “in what way do I represent students’ singing behavior as time series?” DTW itself does not require singing to be standardized; it just tries its best to align the representation you provide. When features allow continuous changes and unstable processes, DTW is actually a very natural, intuitive, and intuition-conforming alignment tool.